A Bivariate Relationship: State and Religion in Nordics

Introduction

From the pre-Christian era to the modern day, religion played a distinctive role in state-building and administrative chapters of Nordic history. State and religion always had an important connection throughout history and in this essay, it will be explained how and why religion in Nordics has become a subordinate pillar of the state. To analyze this phenomenon, the historical interactions between state and religion Nordics will be briefly analyzed from the perspective of subordinate mechanisms. Since this will also allow us to highlight the part when and how the state gained superiority, it will be possible to explain what role had been determined for the religion in Nordic states and what functions it played so far. Finally, the possibility of a change in the future will be discussed and religion’s subordinate status will be highlighted.

Historical interactions between Nordic states and Protestant religion in a brief analysis

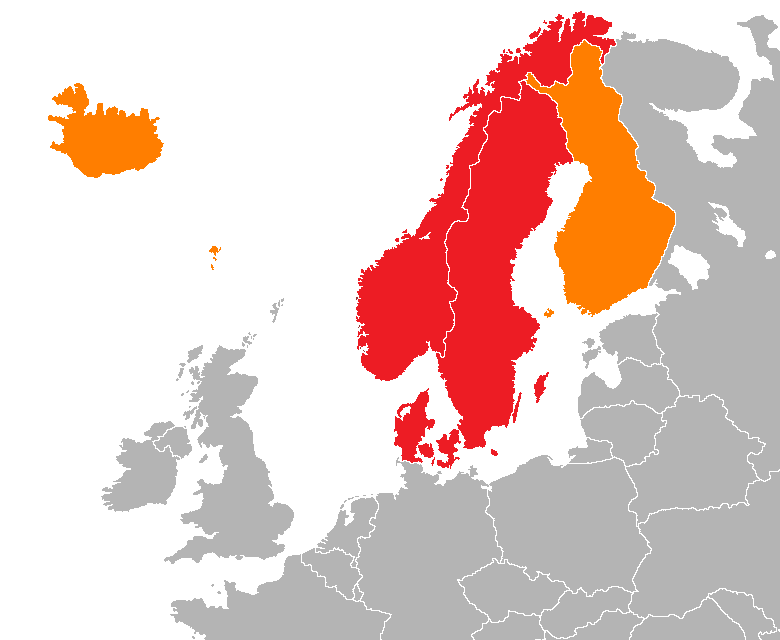

The trend of powershift gradually began with the Protestant Reformation, around the 16th century. Despite the possibility of precious unique phenomenons in the relationship between religion and state in Nordics before this milestone, The Reformation marks the beginning of the change in the status quo. The state and the church were practically merged over time (Strang, 2024); it also was given an administrative and moral role aiming to improve the country with its people (Strang, 2024). Obviously, this transaction did not take place in one way, and in return, the Lutheran Church became a state church tying itself to the royal families over hundreds of years (Bruce, 2000, p. 33). With a similar process whatsoever, the Lutheran Church became dominant in all Nordics and played a similar role. Thus, this hegemony could be the most important explanation of Nordic similarity in terms of welfare and state perception (Markkola&Naumann, 2014, p.8). On the other hand, there was also a difference in Church tradition between Denmark, Norway and Sweden, Finland. The first two countries represented a culture of Low Church and more state control over The Reformation and the other two countries represented a culture of High Church, allowing them to retain a limited level of independence according to Markkola & Naumann (2014, p.10). Nonetheless, all were subject to the state and since we can observe a difference in state control over the church, it means that there is a clear state dominance visible enough to observe. Furthermore, this dominance lasted centuries as the church remained somewhat the same until the 19th century when the democratic reforms forced it to be the church of folk rather than being tied to the royal family (Bruce, 2000, p. 33). Just like how The Reformation allowed the state to be superior to religion, this long-lasting presence shaped religion to become a crucial pillar of the state.

Religion as a subordinate and a pillar in Nordic states

After The Reformation, the power and properties of the church were mostly seized by the state (Strang, 2024), however, it did not lose its importance and role as a factor in Nordic societies. Clearly, the state had to give something back to the church for its obvious empowerment, and thus, the church became a key part of the state’s reach and administration (Strang, 2024). It served as a network to connect to the people and improve their lives as well (Strang, 2024). Furthermore, as the state control over it kept religion under control, centuries spent under this power dynamic proved to be effective and fruitful. Accordingly, Markkola & Naumann explained that Protestantism in Nordics greatly contributed to the welfare system as it allowed the state to control it (2014, p.3). Markkola & Naumann even suggested that the conflicting dynamic between state and church in Catholic-dominated states resulted in a lack of welfare (2014, p.3), especially compared to their Protestant counterparts. To conclude, the state allowed the church to remain active in a key position while the church helped the state in administration as well as contributing to a better and complying society. Still up to this day, these benefits are visible enough to be recognized. In 2013, a study based on state survey data hinted that the members of the respective national churches in Nordics share higher trust in the state compared to the others (Kasselstrand & Eltanani, 2013, p.116), clearly proving the fruits of this cooperation. In a world where the examples of eradication of one side from the power dimension are quite common, this mutual understanding benefits both sides although the state still stays above the other.

Final Remarks

So far, the subordinate role and also the critical pillar position of religion in Nordics and Nordic states are explained. Conversely, the characteristics of the Protestant beliefs should be taken into account above all. It would probably be a completely different situation if Nordic societies believed in another denomination or religion like Catholicism. Nonetheless, theories and thoughts about an alternative history are not a part of political science and history. Up to this day, Nordics remained a distinctive example of state & church cooperation where the state oversaw religion and religion has been a handy factor for the state.

Bibliography

Bruce, S. (2000). The Supply‐Side Model of Religion: The Nordic and Baltic States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 39(1), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/0021-8294.00003

Kasselstrand, I., & Eltanani, M. K. (2013). Church Affiliation and Trust in The State Survey Data Evidence From Four Nordic Countries. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society, 26(2), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn1890-7008-2013-02-01

Markkola, P., & Naumann, I. (2014). Lutheranism and the Nordic Welfare States in Comparison. Journal of Church and State, 56(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcs/cst133

Strang, J. (2024, October 2). Lutheran atheists ?. Centre for Nordic Studies, University of Helsinki. Lecture.

Comments