The Concept of Identity in Türkiye-EU Relations

The European Union, which was founded in the 1950s with the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community and the European Economic Community by six countries (France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg), has pioneered various enlargement and integration processes and interacted with different countries with the significant impact of globalization in the international arena.

With its political and diplomatic steps legal entity[2], the EU has gradually expanded its foreign relations and foreign policy and has become a global actor in world politics. One of the most important reasons for this success of the EU is undoubtedly its enlargement policy, which is constantly revised according to the conditions of the day.

The enlargement of the European Union simply means the accession of new member states. This enlargement process, also known as European Integration, has brought with it various conditions and policies. These conditions are defined by the European Commission (2014) as “The prospect of membership is a strong incentive for democratic and economic reforms in countries wishing to become EU members” (Enlargement Strategy and Main Challenges 2014-15). On the other hand, a country joining the EU must fully meet all membership criteria. However, as one might expect, many country-wide reforms are required to meet these criteria, and this requires a considerable amount of time. For this reason, candidate status has been established for countries that have fulfilled the basic requirements for membership but have not yet fully met all the criteria for membership. Alongside Balkan countries such as Albania, the Republic of North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia, Türkiye is currently a candidate for EU membership.

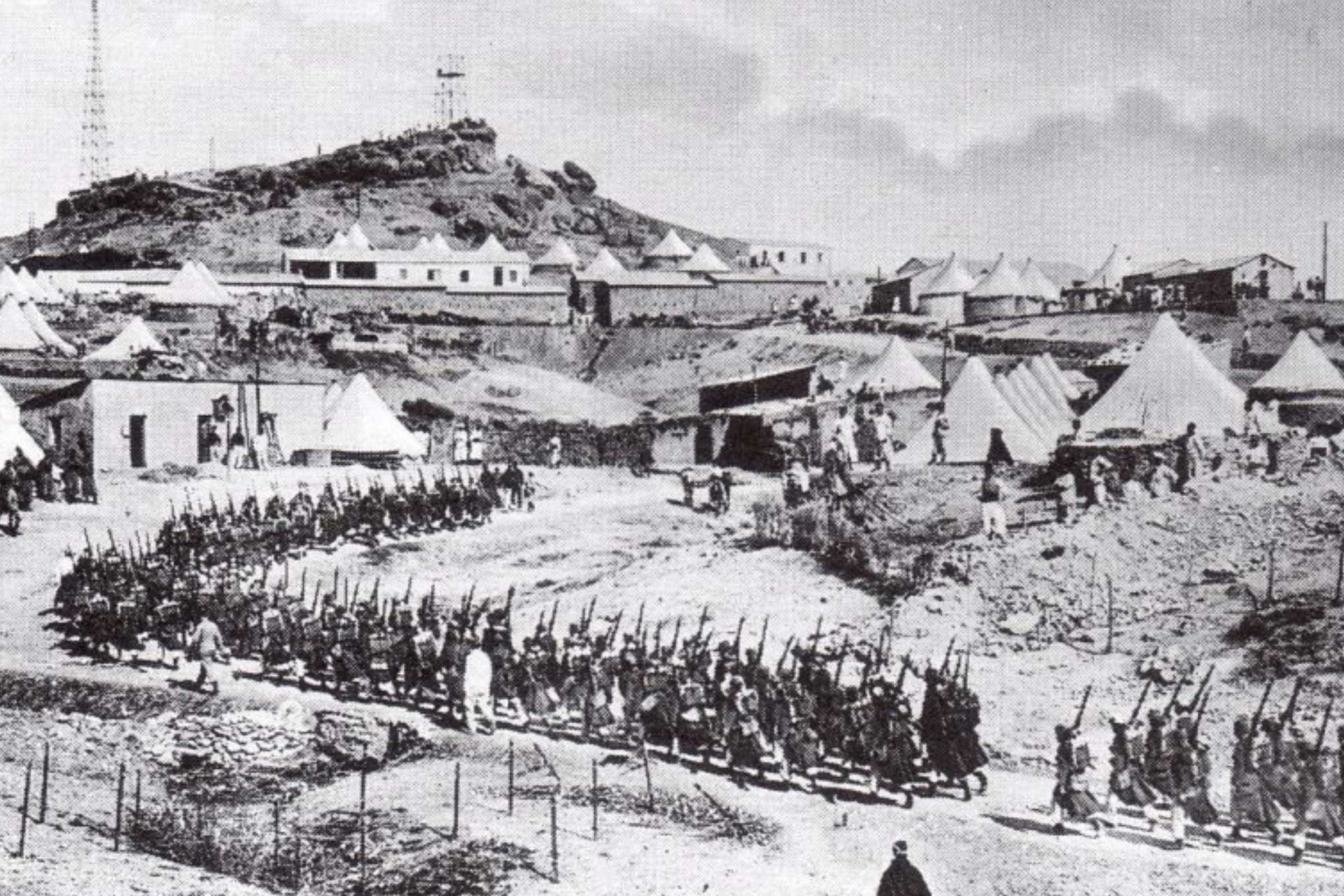

Türkiye-EU relations, which started with Türkiye becoming one of the founding members of the Council of Europe on May 5, 1949, took the name of “Türkiye’s accession process to the European Union” with Türkiye’s application for full membership in 1987 and started to take shape in this direction. With the participation of the coalition government led by Bülent Ecevit, Türkiye was officially granted candidate status at the European Council Meetings held in Helsinki on December 10-11, 1999. In 2002, a new political era began in Türkiye when the Justice and Development Party came to power. Since 2002, various positive and negative agendas have emerged in Türkiye-EU relations and Türkiye has not yet become a member of the EU.

The reasons for Türkiye’s failure to become a member of the EU during the AKP rule can be partially explained by categorizing them under various sub-headings such as democratization, economy, geography and population. However, it is argued that Türkiye, whose membership was suspended with the closure of various chapters in December 2006, has not been able to adapt to the European identity, that is, it has not become Europeanized.

In its simplest definition, identity is the overall image that a country, society or people living in a country (i.e. citizens) project to the outside world through concepts such as distinctive traditions, culture, language, religion, history, ethnicity, nationality and ideology. The reflection can be defined not by the source but by those who see and witness the reflection (Berenskoetter, 2010). In other words, identity, which is integrated with self-perception, is related to how others perceive the society or group in question, which creates a sense of belonging and difference (Kershaw, 2018). Based on the emphasis on difference, the existence of an actor called “other” in the concept of identity is clearly seen (Lebow, 2008).

Throughout history, there have been various formations shaped in line with the sense of belonging of communities. European identity, which is considered important in the relations between Türkiye and the European Union, is one of these formations. European identity is a definition that encompasses the basic values and criteria of the EU in the integration process that came to the agenda after the emergence of the EU as a political union in the international arena.

Despite the many differences within the European Union, common history, symbols and myths have been created and Europeanism is portrayed as a structure that promotes integration, the peace process and regional governance. Division and fragmentation are not tolerated (RUMELİLİ, 2008). Yet Türkiye is even negotiating its own membership goals and what it means to be ‘Turkish’ and ‘European’. In other words, Türkiye is experiencing significant contradictions within itself. Geographically, it is located in both Europe and Asia. A society that predominantly embraces Islamic values coexists with a secular and westernizing state built on the rejection of the Ottoman and Islamic heritage (RUMELİLİ, 2008).

Turkish society is divided between Islamic fundamentalists and secularists, Westerners and nationalists and ummahists. Considering the minority factor and the Turkish-Kurdish conflict sharpened by the PKK and terrorist acts since the 1980s, it is possible to describe Turkish society as “fragmented” (RUMELİLİ, 2008). This emerging dilemma is a confusion that does not please Europe (Düzgit & Rumelili, 2021).

When it comes to the religion factor, the fact that the EU is defined as a Christian Club proves how different the two actors are in terms of religious thought. Starting with the Roman Empire’s adoption of Christianity in the 7th century and fed by various agendas such as 9/11 and the 2005 cartoon crisis, the religious divide has led to the establishment of Islamophobia in Europe (AKDEMİR, 2013). The far right in the EU, referred to as Christian Democrats, has marginalized Türkiye by emphasizing cultural and religious differences and has shown that it is not in favor of Türkiye’s membership (BİREKUL, 2009).

In fact, this religious difference has been an important trump card in Türkiye’s hand in the EU membership process. By referring to the definition of the Christian Club by pointing to religious differences, Türkiye has used the EU’s effort to break away from this identity to its advantage. Since the mid-1980s, strategic arguments for closer EU-Türkiye relations have always portrayed Türkiye as a bulwark against Islamic fundamentalism (RUMELİLİ, 2008). Türkiye’s hybrid identity, articulated by Foreign Minister İsmail Cem in 1997, was adopted by the conservative AKP government that came to power in November 2002. Although secular circles in Türkiye initially opposed the construction of Türkiye as a Muslim Democracy, this eventually became the standard discourse of Turkish foreign policy (RUMELİLİ, 2008). Following Türkiye’s candidacy in 1999, an Islamist political party implemented a comprehensive set of reforms to initiate the accession process, reinforcing the belief that the EU’s decision to grant Türkiye candidate status was the right one. The initial positive changes and the concomitant favorable attitude of Europe started to change over time after the AKP government led by Erdoğan adopted more authoritarian, nationalist and ummahist policies.

In sum, Türkiye claims to be both European and Asian, yet it is an Asian country with strong ties to the Middle East and a continuation of the Ottoman Empire. Europe is not yet ready to accept Türkiye with its current portrayal of Turkish identity. At the same time, the majority of the Turkish population is not in a position to meet the necessary criterion of Europeanization, as this Turkish identity, which includes Islam, does not allow it. As a result, accession negotiations have stalled since 2016. Whatever the diplomatic agenda, an EU foreign policy without Türkiye and a Turkish foreign policy without the EU cannot be imagined. With its geopolitical position, growing population, military power and political presence in the international arena, Türkiye is a crucial actor in the eyes of Europe. Therefore, it is quite possible that these two entities will shake hands again in the coming years.

Omer Valyozoglu

Sources

AKDEMİR, E. (2013). AVRUPA BİRLİĞİ’NDE KİMLİK, Kültür TARTIŞMALARI VE TÜRKİYE. Ekin Yayınları.

Barker, J. P. (2012, April 17-19). Turkish Religious Identity and the Question of European Union Membership. Institute for Cultural Diplomacy: Ankara Conference on Peacebuilding and Conflict Resolution, pp. 1-26.

Berenskoetter, F. (2010, March 1). Identity in International Relations. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies.

BİREKUL, M. (2009). The Rising Culturalist Discourse and Religion Factor in Europe Against Türkiye’s European Union Membership. SUIFD, 69-84.

Commission, E. (2014). Enlargement Strategy and Main Challenges 2014-15. COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS , European Commission.

Düzgit, S. A., & Rumelili, B. (2021). Constructivist Approaches to EU-Türkiye Relations. EU-Türkiye Relations: Theories, Institutions, and Policies, 63-82.

Kershaw, M. (2018, August 7). How National Identity Influences US Foreign Policy. Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 1-5.

Lebow, R. N. (2008). Identity and International Relations. International Relations, 22(4), 473-492.

RUMELİLI, B. (2008). Negotiating Europe: EU-Türkiye Relations from an Identity Perspective. Insight Türkiye, 97-110.

A legal entity is a new and unique person arising from a collection of more than one actor or property coming together around a common interest in accordance with legal regulations. Legal entities include companies, universities, foundations, associations and municipalities. However, the largest legal entity in a country is undoubtedly the state.

Comments