Forced Migration to Türkiye from the Middle East and Türkiye’s Political Stance

The concepts of migrant, asylum seeker and refugee have been confused for years. I would like to start my article by explaining these concepts. A migrant is a person who leaves his/her homeland for good and goes to another country to settle there. An asylum-seeker, on the other hand, is a person who seeks to be admitted to a country as a refugee within the framework of relevant national or international instruments and awaits the outcome of their application for refugee status. [i] While asylum seekers and refugees have problems returning to their country under the current situation, there is no problem for migrants to visit their country. This is because asylum seekers and refugees have left their country for reasons such as oppression, torture and fear of being killed. When we tell someone who cannot differentiate between the words migrant and refugee that Türkiye is not a country that receives a lot of immigration, they will be surprised. The reason for this is that Türkiye is a country that receives many asylum seekers and refugees rather than a country that receives many immigrants. In 72 years (1934-2017), a total of 440,603 families and 1,647,527 people migrated to Türkiye as free and settled migrants.[ii] This number is not sufficient to gain the concept of “country receiving migration”. On the other hand, in 2020, the number of Syrians under temporary protection exceeded 3.6 million.

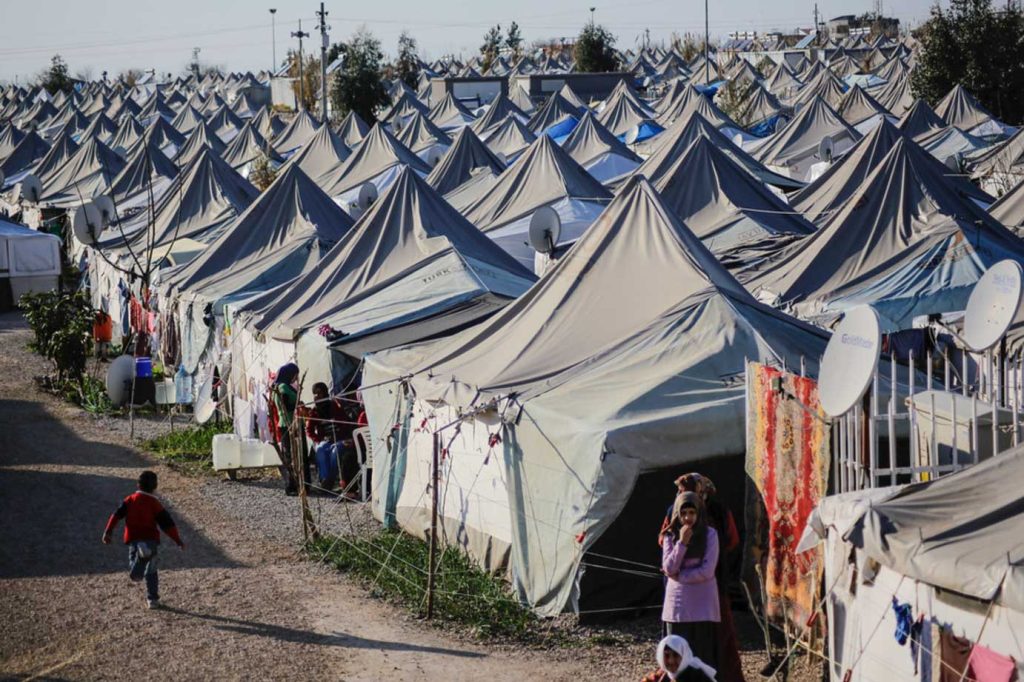

It is normal for people in poverty who are at war in their countries, who cannot find a job in the collapsed economic system, and who are often unable to find a job, to flee their countries and seek asylum in other countries. Within the framework of the “open door” policy, no Syrian who entered Türkiye was sent back and they were granted “temporary protection status”. From the perspective of the country receiving asylum seekers, the “open door” policy brings with it many responsibilities. The following process is more important than the arrival and entry of the refugees to the receiving country. In 2017, Türkiye spent 25 billion dollars for Syrian refugees, despite receiving 588 million euros from the European Union and 455 million dollars from other countries and organizations[iii]. This shows that close to 24 billion dollars of aid has been provided by public institutions, non-governmental organizations and the public for refugees in Türkiye. This is only a material part of the responsibilities that the “open door” policy brings with it. As I mentioned above, I would like to clarify again that refugees do not have the advantage of returning when their numbers become too large in the country of destination. In addition, the national unemployment rate is 13.9 percent and the youth unemployment rate has reached 27.1 percent. [iv] On the other hand, this policy comes with moral responsibilities. Many refugees have been in Türkiye for more than 10 years and continue their lives. We cannot ignore that this situation has many social, economic and cultural consequences.

The fact that countries such as Türkiye, Iran and Pakistan are hosting the vast majority of asylum seekers despite their lack of sufficient economic resources can be attributed to geopolitical location. Asylum-seekers are initially dispersed to neighboring countries, with a smaller majority making their way to Europe and the United States. For example, the US accepted close to 500 Afghan refugees in 2021, 600 in 2020 and 1,200 in 2019. On the other hand, this small number of refugees in relation to the US population is allegedly “racially motivated”. Joe Biden’s decision to ‘exempt incoming Ukrainian refugees from some of the restrictions imposed on other refugees’ may have been effective in this situation.

In line with the above, we can analyze Türkiye’s “Open Door” policy as a humanitarian policy. It is a “humanitarian” policy to accept “stateless” and “stateless” asylum-seekers with temporary protection status while other countries are accepting so few refugees. However, what is important, and what will decide whether the policy is “humanitarian” or not, is the conditions under which asylum-seekers live once they enter the country, rather than the process of their arrival. Given the prevalence of child marriages, child labor and malnutrition, can we really say that this is a fully humanitarian policy? Or can we say that it has a different political motive than “a humanitarian policy” or “temporary protection status” when we consider that 211,908 Syrians and 39,294 Afghan nationals were granted Turkish citizenship and the number of Syrians entitled to vote in the elections was 120,133 [i], according to the statement made by the Population and Citizenship Affairs on August 19, 2022? (The authority to grant citizenship has been taken from the Council of Ministers and given to the President since the transition to the Presidential Government System in 2017). Although the number of people who have been granted citizenship is not remarkable at first glance, those who have been granted citizenship through marriage are starting to attract attention. It is also possible to consider this policy as a modernized version of the ummahist policy that the Ottoman Empire tried to implement in its last periods. Finally, I can say that the Ottoman Empire pursued its policies in line with Ottomanism, ummahism, nationalism and Westernization. If we look at Türkiye’s domestic policies in a broad framework, we can see an attempt at westernization, nationalism and ummahism. I leave it to you to ask whether such policies are realistic and whether they can be successful in a modern and globalized world.

Efsa Demirhan

Undergraduate student-Koç University

[i] https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=5543&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=

[ii] Özdemir, E. (2017). The effects of the Syrian refugee crisis on Türkiye. International Journal of Crisis and Politics Research, 1(3), 114-140.>> http://portal. ubap.org.tr/App_Themes/Dergi/2007-68-290.pdf

[iii] https://www.unhcr.org/tr/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2021/03/3RP-Turkey-Country-Chapter-2021-2022_TR-opt.pdf

[iv] https://www.unhcr.org/tr/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2021/03/3RP-Turkey-Country-Chapter-2021-2022_TR-opt.pdf

Comments