International Conflict and Security Framework: Nagorno-Karabakh from Yesterday to Today

Historical Background

In 1988, the “Nagorno-Karabakh conflict”, which occurred as a result of the independence and annexation movements of Armenian parliamentarians in Karabakh, did not start positively for Armenia; the USSR decided to keep Nagorno-Karabakh as a part of Azerbaijan on July 18, 1988 and directly connected Nagorno-Karabakh to the center in January 1989 (Aydın M. , 2005) (Sapmaz & Sarı, 2012). With the unilateral declaration of independence by Armenians in a referendum on December 28, 1991 and the dissolution of the USSR, the tension between Azerbaijanis and Armenians living in the region rapidly increased and turned into conflicts (SÖKER, 2017) (Svensson, 2009).

- “Ancient hatreds” are a trigger for violent ethnic and internal conflicts. (Brown, 1993) “Ancient hatreds” stem from “old enmities”. As Michael Brown (1993) puts it in his book, “In Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union and elsewhere, these deep-seated animosities have been kept in check by authoritarian rule for decades.”(p. 209) As former US President Bill Clinton argued, the end of the Cold War with the dissolution of the Soviet Union “opened a long-simmering cauldron of hatred” (Brown, 1993).

- Theoretically, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict can be defined as a kind of Melian Dialogue[1] for Armenia. The presence of a powerful ally like Russia has led Armenia to claim Nagorno-Karabakh without any moral and rational justification (Crane, 1998). What motivates Armenia in this conflict are pragmatic goals. In other words, realism overcame idealism.

War Process (External Interventions: Mediation, Peacebuilding)

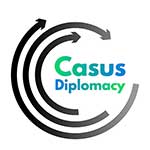

At the OSCE meeting in January 1992, the issue gained an international dimension when Azerbaijan and Armenia became members of this organization. With the decision taken by the OSCE Council of Ministers, the 12-member Minsk Group, including Türkiye, was established. In mid-February, the European Parliament met in Strasbourg and decided to send observers to the region. In February 1992, following a meeting held in Moscow on the initiative of the Russian Foreign Ministry, a ceasefire was agreed upon. On February 24, Iranian Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati visited the region to mediate between the parties. While the parties were trying to agree on the basic issues for a ceasefire, the Khojaly massacre took place, killing more than 600 civilians. The brutal massacre of a large number of people under siege focused international organizations and the world media on the issue. (Doğan, 2020)

- Just War Theory(Just-war theory) As part of international law, war under international law must be morally justified through a set of criteria. These justifications presented by Armenia to the world community, such as “the Nagorno-Karabakh region actually belongs to Armenians” and “the genocide allegation”, serve the jus ad bellum principle of the Just War Theory. In other words, they explain Armenia’s reason for going to war.

The principle of self-determination is of great importance for Azerbaijan, which has become a minority in the Nagorno-Karabakh region as a result of the Armenian policy implemented by Russia over the years. As stated in Article 55 of the United Nations Charter:

“To create the conditions of stability and prosperity necessary for peaceful and friendly relations among nations founded on respect for the principle of equality of rights and self-determination of peoples… ” (UN, 1945).

According to the provisions of the UN Charter, the use of force is prohibited. Considering that threats, armed aggression and intervention are also prohibited, it can be said that Armenia violated many rules. Although the decisions taken by the UN on paper did not have a direct positive effect, joint operations with the OSCE and the Commonwealth of Independent States were successful and a step towards peace was taken and the “Bishkek Protocol” was signed on May 5, 1994. (Aliyev, 2006)

Road to September 27, 2020

Following the Bishkek Protocol, then-President Heydar Aliyev quickly stabilized domestic politics and turned to the resolution of the Karabakh conflict. He also continued to interact with international powers such as the OESC, NATO, the UN and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Under Ilham Aliyev, the Karabakh conflict was again put at the center of foreign policy. The importance of economic development was emphasized to ensure territorial integrity and inviolability of borders. During this period, Azerbaijan focused on developing its foreign relations and making new friends and allies in the international arena, with the aim of making the country visible.

- Despite the positive developments, Azerbaijan could not find the support it expected on Nagorno-Karabakh, so the war for peace(war for peace) began to emphasize the importance of peace. Ilham Aliyev’s approach is a clear sign that if you want peace, prepare for war. “Si vis Pacem, para Bellum” can be paired with

- From the beginning of the conflict, Azerbaijan was the party that wanted peace because the presence of a strong ally like Russia on the other side did not offer any other solution. However, the circumstances that developed in favor of Azerbaijan over time and Armenia’s hard-line stance made Azerbaijan think that peace through war could be a more effective solution.

For this reason, Azerbaijan increased its military expenditures to address potential security challenges and prevented a security dilemma by preventing Armenia from arming itself through a policy of secrecy. During this period, Azerbaijan’s economic and financial activities served as a cover for its armaments. Under Aliyev, the number of states supporting Azerbaijan increased and international organizations adopted resolutions in favor of Azerbaijan. The March 14, 2008 “UN Resolution on the Status of the Occupied Territories of Azerbaijan” clearly demonstrated its success in the international community (Yılmaz, 2013).

Overall Assessment: Fall 2020 and Beyond

Despite concerns in Turkish public opinion at the beginning of the war that history might repeat itself, by October Azerbaijan’s military superiority in the war had misled many. Russia’s more restrained stance and Türkiye’s air force support to Azerbaijan can be cited as the main factors behind this misconception. Moreover, a comparison of the budgets allocated to military expenditures by both countries shows that Azerbaijan spent almost 4 times more than Armenia after the war in 1992. (Sapmaz & Sarı, 2012)

The invisibility of the war process in the Covid-19 pandemic in terms of media and communication factors, Armenia’s isolation and Türkiye’s support may help to understand Azerbaijan’s gains. However, when we look at the factors that led Azerbaijan to victory, the first thing we come across is Azerbaijan’s rightness on this issue.

- As mentioned in the previous section, the moral justification of war is important for winning the support of world public opinion and for international law. The three parts of the Just War Theory, jus ad bellum, jus in bello and jus post bellum, need to be completed with moral justifications. Since Armenia has only completed the jus ad bellum part, which is the right to go to war, it has tarnished its image in international relations through massacres, massacres, harming civilians and even children. However, jus in bello, which describes moral and correct behavior in war, is the most important part of the Just War Theory. Azerbaijan maintained its moral image by not harming civilians during the war.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict may be temporarily resolved, but due to the importance of this region for states, it is quite possible that it will be the scene of another conflict of interest. The recent hot contacts also explain the fate of this region. Russia’s incursion into Ukraine, the growth of China, an economic giant, and the civil unrest in Iran and Syria may remind Azerbaijan that geography is destiny.

Omer Valyozoglu

Sources

Aliyev, T. (2006). Nagorno-Karabakh Question and International Organizations. T.C. ANKARA UNİVERSİTESİTĖSOCIAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ ULUSARASI İLIŞKİLER ANABİLİM DALI, 1-178.

Aydın, M. (2005). “The Nagorno (Upper) Karabakh Problem”, Turkish Foreign Policy,. (B. Oran, Dü.) 2, 401.

Brown, M. E. (1993). Ethnic and Internal Conflicts. In M. E. Brown, Ethnic Conflict and International Security(pp. 209-226).

Crane, G. (1998). Thucydides and the Ancient Simplicity: The Limits of Political Realism. University of California Press.

Dogan, G. E. (2020). The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Assessment of Regional Security. Journal of Security Studies, 167-181.

Dönmez, B. N. (2020, November 27). AN EQUATION WITH MANY UNKNOWNS: The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. icil.org.tr: Retrieved from https://icil.org.tr/cok-bilinmeyenli-bir-denklem-daglik-karabag-sorunu/

Mert, Ö. (2013). ARMENIANS UNDER THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE Ottoman Turks . Recent Period Turkish Studies, 143-174.

Comments