Another Balkan Country on the Road to EU Membership: Albania

Identified as a potential candidate for EU membership during the Thessaloniki European Council in June 2003, Albania submitted its formal application for EU membership in 2009. In October 2012, the European Commission recommended that Albania be granted EU candidate status and Albania was granted candidate status by the EU in 2014. In April 2018, the Commission issued an unconditional proposal to open accession negotiations. In March 2020, the members of the European Council endorsed the General Affairs Council’s decision to open accession negotiations with Albania and in July 2020 the draft negotiating framework was submitted to the Member States. (Commission, 2022) In July 2022, the Intergovernmental Conference on accession negotiations with Albania was held and the Commission launched the screening process. In this paper, the challenges that Albania may face on its path to EU membership will be analyzed against the historical background and international political agenda.

Historical Background

Albania, which was in the Eastern bloc by adopting the socialist ideology during the Cold War, entered a different process in domestic politics and foreign relations with the support of Yugoslavian Communism. In this process, which coincided with Enver Hoxha’s rule, Albania witnessed events such as various infrastructure works (construction of the first railway line), increasing the literacy rate and independent agriculture, as well as the prohibition of religion, private property and foreign travel, the closure of religious facilities and the execution of thousands of dissidents. (Özlem, 2009) By 1967, Albania wrote its name on the stage of history as the“first atheist state.” (Emin, 2014)

The consciousness of democracy in Albania was weakened as a result of Soviet domination and Enver Hoxha’s intention to neutralize the attacks that could be made against his country by destroying the concept of religion at the level of society due to the fact that he saw religion as a weak point against separatist movements from outside. (Özlem, 2009) The intervention of restricting rights and freedoms affecting individuals at the level of society spread to economic freedom and caused Albania to enter into cooperation with big states such as Russia and China. Albania, which became a satellite state as a result of bilateral relations that remained at the level of individuals over time, became closed to the outside world.

By the end of the 20th century, it was clear how unprepared Albania was for the new world order that emerged as a result of the end of the Cold War. The first step towards getting rid of this wreckage was taken on March 31, 1991, when Albania adopted a multi-party system. This was also the beginning of the transition to a pluralist and liberal regime. In the following years, Albania, relatively less affected by the break-up of Yugoslavia and inter-ethnic wars, faced a new reality: The Albanian Diaspora. Although the ethnic mosaic in the Balkans manifested itself in a homogeneous appearance in Albania, the presence of millions of Albanians in neighboring countries such as Macedonia and Kosovo was a concrete example of the Albanian problem in the Balkans.

Until the early 21st century, in parallel with the democratization steps taken in Albania, the European Union, especially after the massacre in Bosnia, made efforts to get rid of its “unskilled” image in the world public opinion. In other words, it has made various moves to prove that it is not only effective in the field of economy by getting rid of the labels of “economic giant, political dwarf, military worm”[2](economic giant, political dwarf, military worm). One of these was the Ohrid Framework Agreement. In 2001, with the participation of EU mediator François Léotard, this agreement, which paved the way for many changes in the field of ethnic rights, brought innovations to the use of languages in Macedonia, and the languages spoken by more than 20% of the country’s population, including Albanian, became official languages along with Macedonian. (BRUNNBAUER, 2002) On January 1, 2008, the visa facilitation and readmission agreements between Albania and the EU entered into force. On 8 November 2010, the Council of the European Union approved visa-free travel to the EU for Albanian citizens and the decision entered into force on 15 December 2010. (Commission, 2022)

International Political Agenda and Assessment

Considering the factors included in the EU membership criteria, such as democratization, economy, population, geography, foreign relations and identity, Albania has to overcome many obstacles on its way to EU membership. As stated by the European Commission (2014), “The prospect of membership is a strong incentive for democratic and economic reforms in countries wishing to join the EU.” (p. 1) Looking at the 2021 Democracy Index Report[3] published by The Economist (ranking the 27 EU member states among themselves), Romania ranks last with a score of 6.43. Albania, described in the same report as a flawed democracy, is even behind Romania with 6.11 points.

In Albania, which has experienced a difficult transition to a free market economy, socio-economic problems are still one of the most preoccupying issues in politics. Albania, which has significant economic potential, has failed to achieve the targeted success in the agriculture, tourism and energy sectors. On the other hand, deficiencies in the fight against corruption and investment security cause foreign investors to remain indifferent. (Emin, 2014)

After 1990, Albania has experienced many political tensions with EU member Greece, and the dispute over the delimitation of the maritime border has a special place for Albania. In 2009, the agreement made by the Albanian government was annulled by the Constitutional Court on the grounds that it was contrary to the country’s interests. In addition, the issue of “Chameria”[4], named after the region in western Greece where Albanians live, is still unresolved. (Emin, 2014)

When it comes to the identity factor, it is quite possible to define Albania, just like Türkiye, as a “torn country”, i.e. a fragmented and divided country. (RUMELİLİ, 2008) Culturally, besides the distinction between Geg (from the North) and Tosk (from the South), more than half of the country’s population are Muslims, 10% are Catholics and 6.7% are Orthodox. The interview given by Edi Rama (2021), the prime minister of Albania, who has taken on the Bektashi heritage from the Ottoman Empire and is still protecting this heritage, can actually be attributed to society at the level of individuals: “I am Catholic, my wife is Muslim. Our two children are Orthodox. Our youngest son can choose the Jewish faith if he wants.’ ‘ (p. 1) It is possible to see this diversity of religious beliefs in the intellectual dimension as well. Enver Hoxha, who is regarded as a tyrant by the religious community, is a great revolutionary and folk hero by others. In other words, it is possible to see statuettes of Enver Hoxha in a souvenir shop in Tirana during the midday prayer.

Considering all these factors, Albania has made considerable progress, but political and economic stability, prosperity and social cohesion have not been achieved. For the EU, which presents a homogeneous outlook, it seems difficult to accept a component that is difficult to integrate and incompatible with the union. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that in international politics and diplomacy, anything is possible.

Omer Valyozoglu

Sources

BRUNNBAUER, U. (2002). The Implementation of the Ohrid Agreement: Ethnic Macedonian Resentments. JEMIE, 1-24.

Commission, E. (2014). Enlargement Strategy and Main Challenges 2014-15. COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS , European Commission.

Commission, E. (2022). European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations. neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu: Retrieved from https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/enlargement-policy/albania_en

Emin, N. (2014). A Guide to Understanding Albanian Politics. Ankara: SETA.

Kershaw, M. (2018, August 7). How National Identity Influences US Foreign Policy. Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 1-5.

Özlem, K. (2009, January 14). Albanians and Albania in the Balkans in the Foreign Policy Axis. Turan-Sam. Retrieved from https://www.turansam.org/makale.php?id=293

Rama, E. (2021, August 26). “I am a Catholic, my wife is a Muslim, and my two children are Orthodox”. Retrieved from https://www.b92.net/eng/news/region.php?yyyy=2021&mm=08&dd=26&nav_id=111547

RUMELİLI, B. (2008). Negotiating Europe: EU-Türkiye Relations from an Identity Perspective. Insight Türkiye, 97-110.

[1] Kuvendi i Republikës së Shqipërisë (Assembly of the Republic of Albania)

[2] The EU is sometimes described as an economic giant and a political dwarf. This description reflects the idea that the EU and its member states have traditionally relied on US leadership and guidance on the most important political and military issues.

[3] The Democracy Index is an index compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). The index is based on 60 indicators grouped into five different categories measuring pluralism, civil liberties and political culture. In addition to a numerical score and ranking, the index categorizes each country into 4 different types: full democracies, imperfect democracies, hybrid regimes and authoritarian regimes.

[4] Denial of rights to Albanian minorities

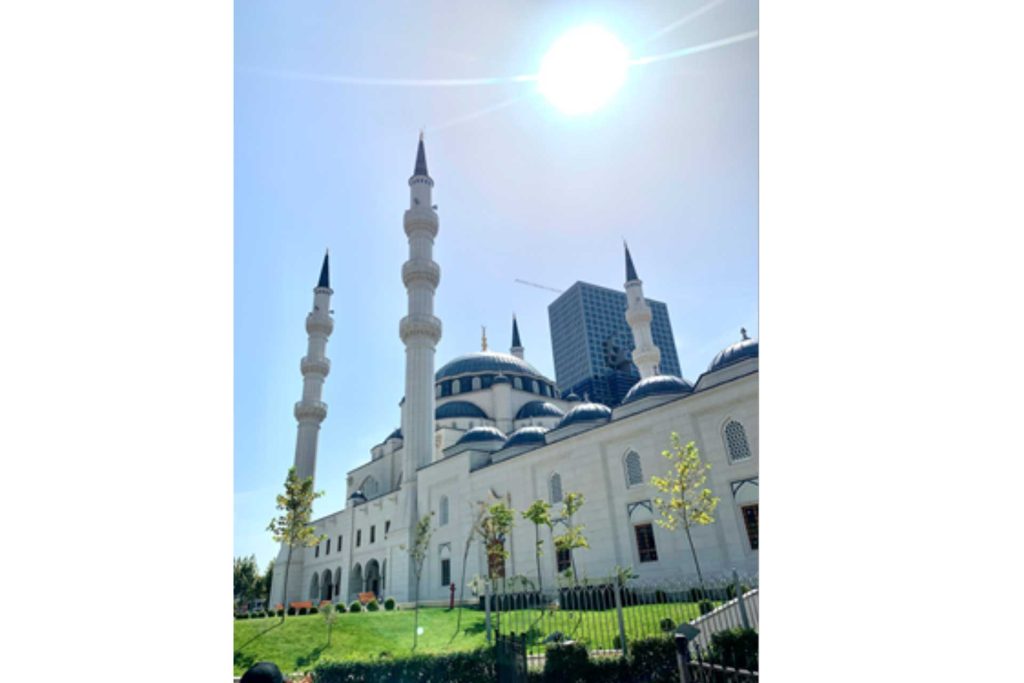

[5] Xhamia e Namazgjasë-Xhamia e Madhe e Tiranës (Namazgâh Câmiî or Great Câmiî of Tirana) is located right next to the parliament.

Comments